The United States is in the midst of an ACL injury epidemic. Tears among high school athletes have increased by 26% over the past 15 years, according to the National ACL Injury Coalition. ACL reconstruction in adolescents is associated with known drawbacks, including postoperative joint instability, muscle weakness and retear rates that can climb as high as 30%. Young athletes are also more likely to return too soon from injury, resulting in increased risk of retear, long-term joint impairment and knee osteoarthritis.

Michael McBrayer, Senior Vice President of Business Development and Professional Relations at Enovis, said the number of kids involved in organized sports has grown significantly, and the emphasis on athletic specialization has them engaged in repetitive movement and physical strain that leads to significant injuries.

The uniqueness of treating injuries in pediatric patients starts with their anatomy. Their growth plates are still open and the biomechanics are different, and recovery trajectories can vary significantly from adults. These factors, McBrayer said, impact how orthopedic companies design products for young athletes.

“I think we’ll continue to see increasing numbers of companies recognize this shift,” he added. “As more physicians are specially trained in pediatric sports medicine and focused on the nuances of treating growing bodies, the industry will need to respond with appropriately designed products, treatment protocols and support systems tailored to this patient population.”

Arthrex’s InternalBrace technique offers a way to lower the risk of ACL reinjuries in young athletes.

Stability for Strengthening

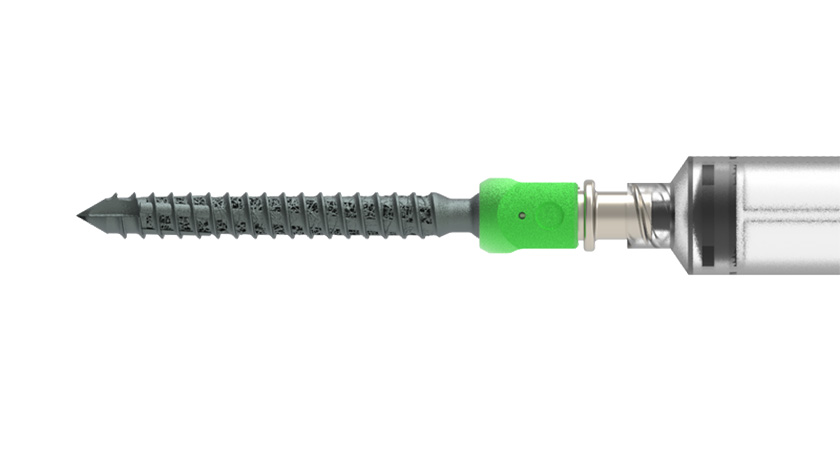

Enter Arthrex’s InternalBrace™ technique, which is designed to reinforce ACL reconstruction during the recovery period of young athletes by positioning a high-strength suture tape alongside the reconstructed graft. It’s sort of a “seatbelt” for healing.

“The tape lies alongside the ACL graft and provides immediate stability while the biological tissue strengthens over time,” said Justin Boyle, Knee Ligament Group Product Manager at Arthrex.

Additionally, the InternalBrace technique facilitates the rehabilitation process by allowing patients to begin bearing weight and moving their knees more quickly after surgery. However, it is not recommended that they attempt a return to activity sooner than is typically advised with traditional ACL reconstruction.

Several new studies have shown that the reinforcement provided by the InternalBrace reduces the retear rates of surgically reconstructed ACLs in young athletes, who often push rehabilitation programs aggressively.

New research also confirms that the InternalBrace technique significantly reduces the rate of reinjuring or retearing a surgically reconstructed ACL. Patrick A. Smith, M.D., a specialist in adolescent ACL reconstruction and repair using the InternalBrace technique, and colleagues conducted a five-year follow-up study of young athletes undergoing ACL reconstruction with a bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) graft.

They found that patients who received suture tape augmentation experienced significantly better outcomes. Among 114 patients under age 19, the group with the InternalBrace technique had zero revision surgeries compared to five in the control group. Additionally, over 85% of patients returned to their original sport at full capacity.

The findings are published in the September 2024 issue of Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery.

“These findings are particularly noteworthy given the high reinjury risk in younger populations,” Dr. Smith said. “The fact that these young InternalBrace patients had intact ACL stability up to 5 years, while actively participating in sports, underscores its long-term protective benefits.”

Boyle noted that Arthrex invested heavily in biomechanical testing and animal safety studies before introducing the device to market. “We want to advance technology that is clinically proven, allows for minimally invasive approaches and helps protect and preserve the natural anatomy of young patients,” he said.

Natural Healing

Miach Orthopaedics takes a more biologic approach to ACL care by restoring the patient’s own ligament through its BEAR (Bridge-Enhanced ACL Restoration) Implant. Rather than harvesting a tendon graft, the BEAR Implant provides a resorbable scaffold that supports the torn ACL as it heals in place.

In March, the BEAR Implant received FDA clearance to expand its indication to include children and adolescents 2 to 14 years old, as well as to treat partial ACL tears. The BEAR Implant previously received De Novo Approval in 2020 to treat skeletally mature patients at least 14 years of age with complete ACL tears.

“ACL reconstruction is often a much more complicated procedure in a growing child than it is in an adult because of their open growth plates,” said Arjun Ishwar, Vice President, Commercial at Miach Orthopaedics. “The BEAR Implant offers a more natural solution to ACL injuries and works with a child’s body as the musculoskeletal system continues to develop.”

Ishwar said traditional ACL reconstruction includes several limitations, including donor-site morbidity, muscle weakness and added recovery challenges. He noted that ACL reconstruction also replaces rather than restores the native ligament, leading to loss of proprioceptive fibers and less natural knee biomechanics.

These factors contribute to higher re-injury rates, residual joint instability and an increased risk of early osteoarthritis in young or highly active patients.

Still, Ishwar said, ACL repair is experiencing a resurgence even though its use is often limited to certain types of ACL tears, mainly proximal avulsions and proximal tears.

“The BEAR Implant can be used on nearly all tear types, from proximal avulsions to distal tears, and it is also used by many surgeons in primary repair procedures to facilitate a more natural healing environment,” Ishwar said.

Maintaining native anatomy during ACL reconstruction is crucial because it preserves the knee’s stability, normal biomechanics and proprioception, and it may reduce the risks of re-injury.

“The BEAR Implant supports this by allowing the healing of the patient’s own ACL within its natural footprint, maintaining native tissue and neurosensory fibers,” Ishwar said.

Martha Murray, M.D., a sports medicine specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital, developed the BEAR Implant and a standardized surgical technique that was used in the BEAR I and II studies and included in the submission package to FDA for the De Novo approval. The BEAR I study assessed the safety and efficacy of the BEAR Implant; the BEAR II study compared its performance to ACL reconstruction using autologous hamstring tissue.

“Because the surgical approach for the BEAR Implant was so different than anything that had ever been done for ACL tears, it was important to have a standardized technique (during the Bear I and Bear II studies) for ease of learning and reproducible results,” said Ishwar, who added that the surgical technique has evolved over time as surgeons apply their individual expertise to the procedure.

“In our Bridge Registry, which is studying real-world use of the BEAR Implant, surgeons are allowed to explore different fixation and suture materials,” Ishwar said. “With these varying techniques, we are seeing a low overall retear rate of around 5% at two-year follow-up for the first 100 patients, which is lower than the published rate of 14% in the BEAR II study. Study surgeons theorize that this is due in part to the technique modifications.”

Jacqueline Brady, M.D., Associate Residency Program Director and Surgical Director of Sports Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, is co-principal investigator of the Bridge Registry.

More than 5,000 patients were treated as part of the Bridge Registry as of March. Dr. Brady said surgeons have modified the surgical technique by using buttons instead of anchors and strong sutures over absorbable ones or suture tape. After one year of data, the overall reoperation rate in the first 96 patients in the registry was 8.4% and included two retears.

In July, the Cleveland Clinic completed enrollment in the BEAR MOON study, a randomized, controlled clinical trial conducted at six clinical centers of excellence. The study’s aim is to compare the BEAR Implant to autograft BPTB ACL reconstruction in 150 patients between 18 and 55 years of age with complete ACL tears.

“Many surgeons consider BPTB to be the standard of care for ACL reconstruction, and previous studies compared the BEAR Implant to hamstring autograft,” Ishwar said. “We expect that the results of BEAR MOON will build on the significant body of clinical evidence for the BEAR Implant that now exceeds 10 years.”

Ishwar believes ACL management will become more personalized and biology-first over the next decade, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all reliance on repair. He pointed out that many surgeons now consent patients for both the BEAR Implant and reconstruction, deciding in the O.R. which option best fits the injury.

“That flexibility reflects the future and will preserve native tissue and proprioception, reduce morbidity and improve outcomes for patients,” Ishwar said.

DC

Dan Cook is a Senior Editor at ORTHOWORLD. He develops content focused on important industry trends, top thought leaders and innovative technologies.