When an ACL tears, the standard of care for treatment in the past 30 years has been either an autograft or allograft reconstruction, both of which pose significant problems. With autograft reconstruction, a surgeon removes the torn ACL, and then a replacement ligament is harvested from another part of the body, typically the patella tendon or hamstring.

This means a second wound is created to repair the first one, and there are often comorbidities. When another tendon is harvested, the tendon’s different size and configuration is not meant to be in the ACL joint. The surgeon may have to manipulate the tendon to fit the space.

Allografts use tissue harvested from a deceased donor. There is inconsistency with the tissue depending upon the age of the donor and quality of the tissue that the patient will receive. In either case, misalignment is a risk, meaning that the knee will never again work the way it is supposed to. The process has been ripe for innovation.

One of the significant facets to a functioning ACL after injury focuses not just on the method of repair, but also on what it takes for the ligament to heal. Understanding the anatomical complexities surrounding the ACL, coupled with a basic understanding of how the body heals itself, has helped unlock the key to a new approach.

The Source of the Challenge

Martha Murray, M.D., Founder, Miach Orthopaedics and professor of orthopedic surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, spent years studying why effective, patient-friendly ACL repair remained elusive. Her research examined the similarities and differences between how the knee ligaments reacted to injury and how they healed.

The knee’s major ligaments—PCL, MCL, LCL and ACL—do not all heal in the same ways. MCL and LCL can heal without surgical intervention, while the ACL cannot. As such, ACL injuries often leave patients with long-term limitations, and many never regain their pre-injury strength and mobility, even after surgery.

Blood clots became the central focus of Dr. Murray’s research. A clot is necessary for healing, because the clot releases growth factors, which allows for new collagen formation for the ligament to heal. The MCL is in an extra-articular space, and a blood clot can form. But with the ACL, because of the type of fluid in the knee joint, a blood clot cannot form.

For decades, Dr. Murray studied the ACL’s hostile environment and sought answers. She needed to develop a technology that would protect the blood so that it could clot in the ACL space.

“There were many years spent developing the technology that not only would protect the blood from being degraded and removed, but she also had to balance the notion that the blood vessels and the fibroblasts needed to grow in,” said Martha Shadan, President and CEO of Miach Orthopaedics. “They were attracted by the blood clot and they needed to grow in to be able to do their job.”

Dr. Murray established Miach Orthopaedics as a privately-held company that built on her research to develop bio-engineered surgical implants for connective tissue repair. Homing in on the ACL’s limitations to repair itself naturally, Miach Orthopaedics aimed to mimic the natural healing of other knee ligaments through a novel implant.

Breakthrough Technology

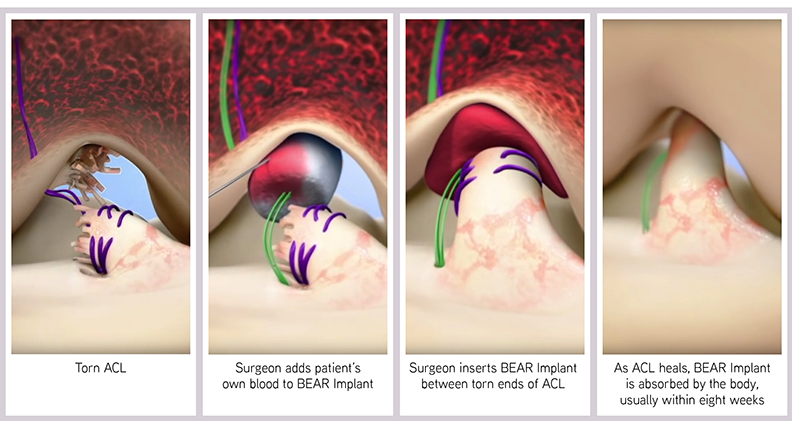

The Bridge-Enhanced ACL Repair (BEAR®) Implant was the result. Bovine tissue is highly cleaned, purified and shaped into a cylindrical implant about 45 millimeters long and one inch wide. It is very porous, allowing for cells to move into the implant and absorb the proteins in the implant. A blood clot is then able to form, and growth factors are released to start the process of healing.

“We create a favorable healing environment, and then the body takes over and it heals,” Shadan said. “We’re not necessarily healing the ligament; we’re allowing the body to do its job.”

The BEAR Implant is injected with the patient’s blood during surgery. It is inserted between the torn ends of the ACL and stabilized by suturing it to the femur and the tibia. It’s not sutured to the torn ACL, but rather nestled in next to the ligament. The torn ACL remains in place, retaining the natural insertion points of the native ACL. As the two ends come together and heal, the insertion points are not disrupted and the ACL is restored to its natural anatomy and position within the knee.

“As the new collagen starts growing, the implant itself is reabsorbed and it goes away within eight weeks,” Shadan said. “So it’s not permanent. It’s there to do a job and then it goes away so you’re not left with things you don’t want in your body.”

Beyond the biological issues, the challenge was to develop a surgical technique that was straightforward, repeatable and effective in stabilizing the knee while new collagen tissue was produced. Dr. Murray performed a number of design experiments to test parameters in an iterative approach. In the process, she published more than 35 animal studies to validate that the implant and the technique worked.

By 4Q18, the BEAR Implant had been designed and Miach Orthopaedics made small clinical lots at Boston Children’s Hospital. The company was in the follow-up period in clinical trials. By mid-2020, Miach Orthopaedics submitted their De Novo application to FDA. Less than six months later, FDA granted the De Novo request for the BEAR Implant, resulting in marketing approval for the treatment of ACL tears, one of the most common knee injuries in the U.S. Miach Orthopaedics is the first company to receive a De Novo for an orthopedic sports medicine implant.

The BEAR Implant is the first medical technology to clinically demonstrate that it can restore the native ACL without having to replace or reconstruct it.

“This has been a long-time goal, because surgeons know that if you can restore the native anatomy, it’s better for the patient, it’s better for the knee kinetics, it’s better for the overall performance of the knee,” Shadan said. “Compared with autograft ACL reconstruction, the BEAR Implant showed faster recovery of muscle strength and higher patient satisfaction with regard to readiness to return to sports and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score measures of pain and symptoms. We are not surprised, because it is less invasive than reconstruction, where they’re drilling bigger tunnels or holes. Ours are much smaller, and we’re not creating that second wound. It’s a much less intrusive procedure.”

Approximately 400,000 ACL injuries occur in the U.S. each year, and a large portion of patients do not ever regain full function of their knee. Miach Orthopaedics is continuing their research to determine if there is a long-term benefit that the BEAR Implant provides outside of ACL repair itself.

“There is a very high percentage of people who develop osteoarthritis (OA) after reconstruction, and the reasons for that aren’t fully understood,” Shadan said. “But we do believe that if the ACL isn’t restored to its native position and performance, that could lead to OA. So with all of our clinical studies, we are continuing to follow patients out to six and 10 years because in preclinical studies, we saw no OA developed in the animals with the BEAR Implant. But we did see it with the animals that weren’t treated with it.”

Currently, Miach Orthopaedics is monitoring the ongoing situation with the COVID-19 pandemic to determine the best time to launch. They plan on a limited market release in 2021 with orthopedic surgeons who have a high volume of ACL procedures, such as sports medicine surgeons, and those who are at the forefront of innovative technologies.

Since announcing the De Novo approval, Miach Orthopaedics has received enormous outreach from surgeons and patients.

“On a daily basis, we’re getting requests, which is a sign that there is pent up demand for technology that restores rather than reconstructs,” Shadan said. “There’s a lot of excitement out there. We believe it to be a platform technology that has applications in other anatomies. We’re going to focus on the ACL initially and create adoption with it for ACL, but we’ll be looking at other applications as well.”

HT

Heather Tunstall is a BONEZONE Contributor.