Orthopedic companies are consistently adopting additive manufacturing, proving its viability in the industry. Whether a device company is incorporating the technology for the first time or expanding its capabilities, it must choose a platform and decide to insource or outsource the manufacturing.

“As I look across the orthopedic industry, the top 10 orthopedic companies currently have in-house additive manufacturing,” said Chuck Hansford, Director of Advanced Development at Tecomet. “The top 20 are utilizing additive manufacturing, either contracting it out or looking at purchasing and bringing the technology internal.”

Small orthopedic companies are also heavily invested in additive manufacturing.

“It’s a necessity, and it’s going to continue to grow,” said Cambre Kelly, Ph.D., Chief Technology Officer at restor3d, which 3D prints patient-specific implants.

Nexxt Spine, an early adopter and prolific user of additive manufacturing, 3D prints nearly all of its implants. “Additive gives you a much broader breadth of types of products,” said Andy Elsbury, Nexxt Spine’s President. “You can design intricacies with the capabilities.”

The design advantages additive manufacturing brings to orthopedics are well noted. Beyond the design, additive manufacturing adoption is highly complex, and OEMs should seek advice from external partners on matching the right technology to their strategy.

Finding the Right Fit

Powder bed fusion methods that use electron beams or lasers are well-established technologies in the orthopedic market. Machine manufacturers like 3D Systems, EOS and GE Additive have differentiated and proprietary capabilities, making it essential that orthopedic companies perform due diligence when deciding which method best matches the needs of their device and their overall additive manufacturing strategy.

Companies should look beyond a machine’s spec list, including the sticker price and number of lasers, said Davy Orye, Team Manager of Additive Minds Consulting at EOS. To be successful, companies must consider the best application for their implant design, the cost of developing and manufacturing the implant, including post-processing and supply chain efforts, and the support and expertise of external partners.

“It’s not plug-and-play technology. Always keep that in mind when making your decisions,” Orye said. “There’s still an art to 3D printing.”

The technologies on the market are fundamentally different processes, said Martin Petrak, CEO at PADM Group. Orthopedic companies need to match their application to a process and a strategy. “It all comes down to your business case,” he said. “We typically want to pick the best process for the application and then the best application for the business model.”

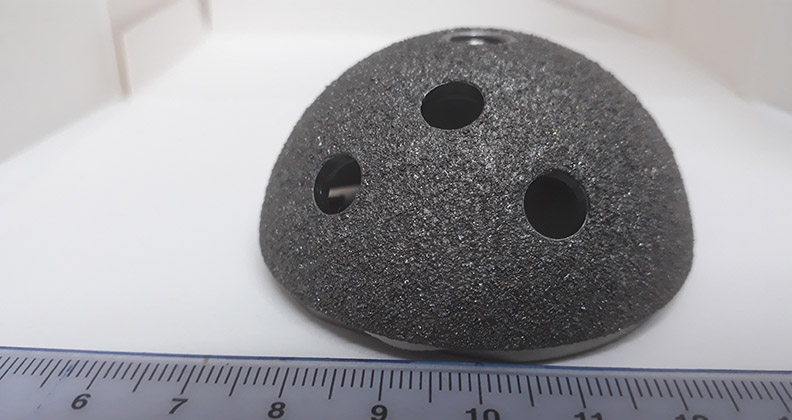

ARCH Additive uses GE Additive’s electron beam melting (EBM) and EOS’s direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) machines. Brian McLaughlin, President at ARCH Additive, said that companies must ask themselves a list of questions about their desired implant when deciding on an additive manufacturing process. These include the size and roughness of the implant, the amount of inventory they plan to produce and their post-processing capabilities.

He said that laser printing usually provides a smoother surface, about 200 microns, compared to 300 microns with EBM. Implants can be stacked in EBM chambers, allowing for more devices to be manufactured simultaneously.

“Probably 60% to 70% of the spine market is using laser, and that has a lot to do with the size of the implant,” McLaughlin said. “Small- and mid-sized companies can print a good chunk of inventory on a single platform based on the size. Think cervical implants — pretty small. You can print several hundred on a single-layer build.”

In contrast, McLaughlin believes that EBM is the better choice for large joints, though he noted that both technologies are used across orthopedic applications.

McLaughlin also advised that companies consider what additive manufacturing technology their competitors and supplier partners use for similar devices. What type of products do they design and manufacture? What software do they use to design implants?

“You want to go into this with an understanding of the software that you’re going to use, how you’re going to prepare your design, how you’re going to bring it over to the platform, and then how you’re going to start your machine,” he said. “After you’ve machined your implant, what type of analytics and data do you get to tell you how well the build performed or how good the parts are?”

Deciding to Insource vs. Outsource

The decision to insource or outsource any manufacturing process comes down to the cost of buying machines and building expertise. There is a universal understanding that machines are expensive. Where companies underestimate their investment in additive manufacturing is the time and expense needed to develop their process and quality management system.

According to OEMs and contract manufacturers in the space, manufacturers need to spend two to three years to become proficient in the technology if they want to bring it in-house.

Nexxt Spine outsourced its additive manufacturing while it proved its technology concept. As the company expanded its product development, it made more sense to bring the manufacturing in-house. Elsbury said it took the company nearly three years with the machine on the floor to fully understand how to print products.

“Our decision to insource was all about the speed and quality of the outcome,” Elsbury said. “Contract manufacturing absolutely has a place. It takes years to be good at additive manufacturing. In-house is much faster, but you’ve got to be in it for the long term.”

restor3d also chose to insource because of the up-front energy it took to solidify internal tribal knowledge, Dr. Kelly said. The company’s R&D engineering team benefited from iterating implant designs and seeing what worked and failed in real time.

“We definitely learned that these machines are not plug and play and there are a lot of ways to print really good parts but also really bad parts,” Dr. Kelly said. “It was a cost and lead time position that interested us in owning the manufacturing end to end.”

Dr. Kelly noted that the only reason restor3d would potentially outsource its additive manufacturing is if it needed to scale faster than it could internally.

Elsbury said Nexxt Spine has no intention of outsourcing its manufacturing because adding a machine is not as difficult as starting the process with a new supplier. “Plus, you control the cost, lead time and quality,” he said. “All of the above is why we’re keeping it in-house.”

It will, of course, make sense for some companies to outsource their additive manufacturing. PADM Group has helped large companies that wanted to develop products on multiple platforms or scale rapidly and small companies that needed guidance during design or regulatory stages.

“There has to be a business model that makes sense to use additive manufacturing and a partner like ourselves in the process. It’s usually speed to market,” Petrak said. “We’re very nimble. We’re able to understand the core basis of your functional requirements from an orthopedic perspective and potentially from the end-use customer, which is going to be the surgeon.”

Elsbury noted that a primary advantage to using a contract manufacturer and leveraging the expertise of machine companies is that they’ve developed deep and diverse knowledge from working with numerous orthopedic companies over the years. Further, additive manufacturing machine companies like 3D Systems, EOS and GE Additive have expanded their offerings and developed relationships with contract manufacturers to provide broad-based solutions.

“We believe that an end-to-end solution is actually what larger organizations are going to start requesting, because they want to focus their business on their clients and on data,” said Petrak, whose organization partners with Tecomet and EOS. “This is where we must become a little more sophisticated and have that holistic offering. It is becoming more of a trend.”

Transferring Processes

Orthopedic companies are often machine or method agnostic when adopting an additive manufacturing technology due to investments in equipment, knowledge and regulatory requirements. It is possible to transfer some additively manufactured implants to a new system, but it can be time intensive.

“They are fundamentally different processes,” Petrak said about additive manufacturing systems. “You must design to the process, design for the subtractive process and design for different thermal gradients. You have to think about all these pieces when designing your components.”

Orye said he has transferred EBM and other laser methods to EOS machines, but that transition won’t work in every instance. For example, EBM and laser machines produce different resolutions, so a company might need to alter its design to accommodate the change.

“It comes down to ‘like’ transferring,” Orye said. “I’ve seen projects in which part of the implant was first printed on other technology, and then the client said, ‘We want to move it to your technology.’ When you transfer to other technologies, you must have application and equipment knowledge to understand the differences. Then you can adapt your process accordingly.”

Dr. Kelly said restor3d is cross-qualifying multiple systems. The company’s knowledge is deep with one system, and they recognized early on that their understanding wouldn’t transfer one-to-one to the new system. They used their old CAD file on the new system to get a baseline for the transfer, and the print failed quickly.

“It’s a learning process,” Dr. Kelly said. “You have to go into it with your eyes open and know it might not print perfectly the first time.”

restor3d recognizes that companies will invest in new technology as additive manufacturing advances. “Typically, companies invest in one printer technology, and then stay with it because they feel locked in. Particularly from a regulatory standpoint, they feel they need to prove to FDA that they’re producing equivalent parts,” Dr. Kelly said. “We’re trying to be printer agnostic and continue to adopt the evolving technology.”

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.